The artist’s currency has no use for archaic monetary systems, financial deregulation or distorted construction value. It’s a new form of political subversion, as proven by initiatives in South America that are reinventing the rules for spreading culture.

Photo: © Gustavo Romano

Instead of complaining about oppression and lack of money, activists have been creating alternative currencies and financial circuits that propose a new approach to capital. Bitcoin stands out among these alternatives as a currency that is not issued by a Central Bank and exists only on the internet, where it can be accumulated as digital files. It may seem lighthearted, like Monopoly money, but bitcoin is currently listed at over €400 at today’s official exchange rate (1). Bitcoin is not the only existing modern currency alternative, nor is this area of activity merely the domain of hackers and financial market experts.

Without worrying about encryption or investment grants, artists are creating imaginary currencies, as well as their own banks and systems that propose alternatives to macroeconomic models. Through a wide range of critical initiatives, they seek to establish new rules for the circulation of culture, using their own money to mimic value creation processes and as a device for political subversion.

Alternative currency as a collaborative methodology

One of the first collaborative currency experiments was conducted in Brazil, back in 2005. This was the now famous and controversial Cubo Card, issued by Circuito Fora do Eixo. It was a brave attempt aiming to be a parallel currency developed by cultural producers and artists to fund artistic and cultural production.

Without sufficient funds to finance the demand of music bands in Cuiabá (capital of Mato Grosso do Sul, in Brazil’s Midwest region), the cooperative enterprise Cubo decided to create its own currency–the Cubo Card–which it used to pay bands and in exchange for other services (press releases, website, rehearsal time in the studio etc). « We started distributing Cubo Cards very enthusiastically, particularly as all those who witnessed the experiment we were conducting wanted to be part of it, recognizing its value. By producing Cards, Cards and more Cards, we got to the end of the year and found that a large number of people were requesting their services at once. We had a subprime product! » says one of its creators, Pablo Capilé.

Photo: © Gustavo Romano

This kind of initiative, regardless of its success or failure, is especially important from a methodological point of view, shifting the debate on the cultural market towards reflection on market culture. However, the most promising attempts in this field may have been by artists who, rather than attempting to create new market formats, have been able to reinvent them, expanding the boundaries of economic thought and practice. By comparing their values and mocking symbols of efficiency, they highlight the authority of their organizational parameters, like the Argentine artist and curator Gustavo Romano in Time Notes, an ongoing project since 2010.

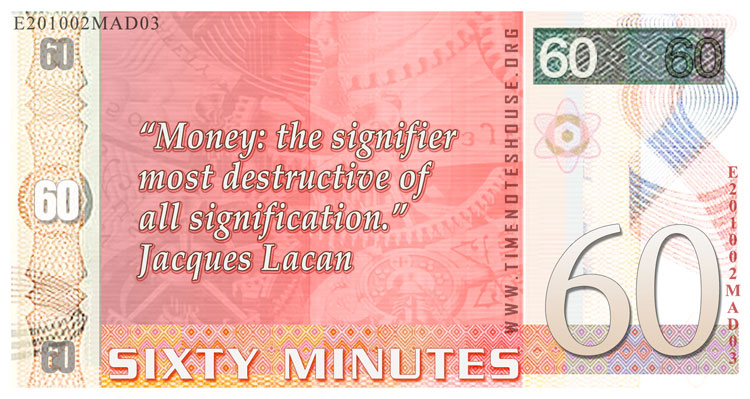

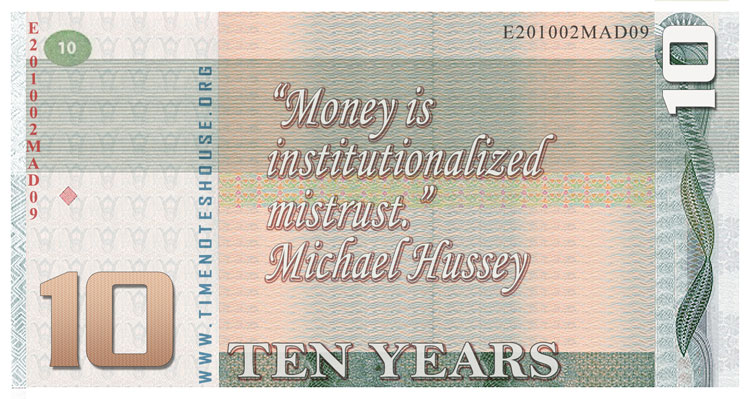

An imaginary currency as a critical device

It is commonly said that time is money, but in the case of Romano’s project, this saying is law. He created a database which allows you to catch up, borrow time and query the database about wasted time. In one year he set up offices for this banking network in Singapore, Berlin, Buenos Aires, São Paulo, Madrid and numerous other cities.

The project is an offshoot of a more extensive survey by the artist, the nomad global issue discussion lab known as Pshychoeconomy. Romano exhibited this work at the World Bank building in Washington, where he presented his thesis. The final report on the experience can be read in the e-book Mis 10 Días como Consultor del Banco Mundial, available for download at http://www.timenoteshouse.org/.

Romano’s subtle irony with regards to the financial market has its equivalent in the smaller world of art. After all, very few industries seem to enjoy paying to be criticized as much as art collectors. At least that’s what the work of Brazilian artist Lourival Cuquinha appears to show. He highlights the creation of monetary values in art in several of his projects and dedicates himself to what he calls financial art.

Two of his recent installations explain this relationship: an enormous asterisk consisting of rods made up of five-cent Brazilian Real coins–the lowest-denomination Brazilian coin in circulation–had to go for millions at ArtRio, the Rio de Janeiro art fair, in September 2014. This work was first shown at Cuquinha’s solo show at the Modern Art Museum of Rio de Janeiro, in June 2014.

Photo: © Lourival Cuquinha

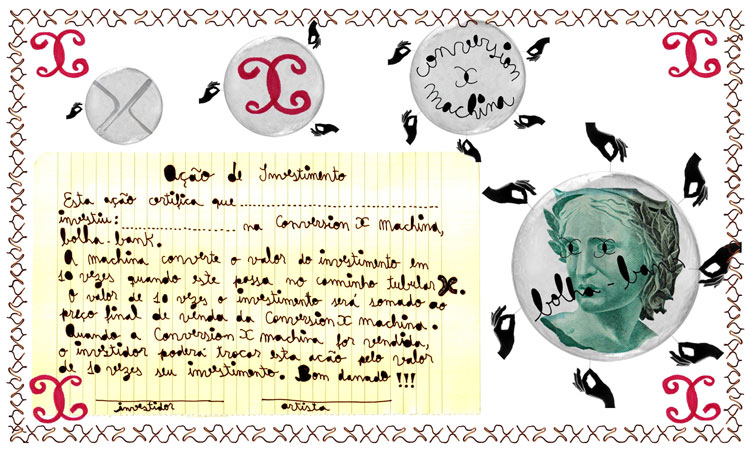

In 2013, the same art fair showed Cuquinha’s Conversion x Machina Bolha Bank (2013), a work that satirized procedures that give art pieces an investment status, placing the financial and art markets on equal footing. In order to achieve this, the artist created a machine based on a banknote vacuum, in which investments in the work were deposited. This investment entitled one to purchase shares guaranteed to multiply tenfold in value if the work was sold.

Each investor also received a wooden plaque signed by Cuquinha, which acted as a share redemption document. The more shares were sold, the more the value of the work went up. Launched in September 2013 at the ArtRio fair, the installation was initially valued at €15,000, a price calculated by multiplying the cost of producing the work (€1,500) by ten. From there, two links between the work and the show were possible. The installation could either be purchased in full for its original price, or those interested in profiting from the sale could purchase shares that were both pieces of the bubble bank and bets on its future sale.

Shares were priced between €17 and €1,000 and represented a refined metaphor for financial market bubbles. The more shares you bought, the more the price of the work went up. Each amount invested in the money vacuum was automatically multiplied by ten, thereby increasing the value of the work. By the end of the Art Fair, the work was worth €80,000.

Money circulation as a political subversion device

Not all artists who deal with money in their works do so to reflect directly on market issues. One of the most important works in the history of Brazilian art, Inserções em Circuitos Ideológicos, by Cildo Meireles, is evidence of this. Created in 1970, during the cruelest period of the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964-1985), Meireles used it to re-appropriate everyday objects, symbolically modifying them and re-launching them on the market, an example being Coca Cola bottles featuring the printed phrase Yankees go home.

Of all the Inserções, none is more relevant to our discussion than that which had the question “Quem matou Herzog?” (« Who Killed Herzog? ») stamped on Brazilian one cruzeiro notes, the lowest currency value at the time (1970’s). Meireles replicated a ritual that was common in Brazil, particularly among the low income population, which consisted of writing wishes, messages, prayers and promises on banknotes that circulated endlessly. He adopted this Brazilian ritual to question the death of an important political journalist, Vladimir Herzog, who was murdered under torture by the Military Police and whose death was attributed to suicide, showing a forged photograph.

This work recently returned with the question “Onde está o Amarildo?” (« Where is Amarildo? ») stamped on the current lowest-denomination Brazilian banknote, the two real note. A construction worker who disappeared on July 14, 2013, after being stopped by the Polícia Pacificadora (Police Pacification Unit) at the Rocinha slum in Rio de Janeiro, Amarildo’s « disappearance » reintroduces the question at the heart of the work Inserções em Circuitos Ideológicos: where is the public sphere in Brazil? Who is entitled to it? Which classes are granted the freedom to come and go in Brazil’s public space?

Giselle Beiguelman

published in MCD #76, “Changer l’argent”, déc. 2014 / févr. 2015

Giselle Beiguelman is an artist and professor at the College of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of São Paulo, where she coordinates the Design course.

This article revisits and updates the ideas presented in “A arte de fabricar dinheiro” (“The Art of Producing Money”) and “Daquilo que não se vende” (“That Which is not Sold”), published in the journal SELECT, editions 1 and 14.

(1) August 8, 2014.