Co-founder of Makerspace Madrid, Cesar Garcia Saez also hosts La Hora Maker, a media & YouTube channel followed by more than 5000 makers in Spain. For Makery, he comes back on the mobilization of the makers in support of health care workers and exposed personnel during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Medical Personnel at Terrasa Hospitals wearing 3D printed faceshields produced at Tinkerers Fablab Casteldefels. Photo: D.R.

Spain was one of first European countries to be hit by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, right after Italy. By March 14, the Spanish government declared a State of Alarm and mandated a nationwide lockdown. During the three months that followed, both ad hoc and existing teams of Spanish makers have been communicating, organizing and working remotely to respond to the crisis.

Before the lockdown

During the weeks leading up to the State of Emergency in Spain, news from Italy and China highlighted the urgent need for lung ventilators to treat patients in Intensive Care Units. Without any corrective measures, the exponential nature of contagion threatened to provoke a peak demand for these devices, and many more potential deaths.

Realizing the critical nature of this problem, several groups around the world started working on open source solutions. In response to Colin Keogh’s call to develop an Open Source Ventilator on Twitter on March 11, a dedicated group was created on Telegram, parallel to the existing Facebook group, specifically to unite Spanish makers who preferred to collaborate through the popular messaging app.

At the same time, Jorge Barrero, director of COTEC Foundation for Innovation, called on several members of its network (including the author of this article) to evaluate the feasibility of a low-cost 3D-printed ventilator. After receiving positive feedback from several sources, in addition to news about a “small” group of makers tackling the problem, another initiative was born: A.I.RE (Ayuda Innovadora a la Respiración / Innovative Help for Breathing), a WhatsApp group to connect anyone able and willing to help, including doctors, enterprises, makers, innovators, etc.

As for the “small” maker group—Coronavirus Makers—it spread like wildfire among the Spanish maker community. In the weekend before lockdown, the Telegram group grew to 1,000 members in less than 48 hours. Just two weeks later, it expanded to 16,500 members! But how does a community with thousands of members organize?

Volunteers assembling 3D printed face shields at Fab Lab Sant Cugat. Photo: D.R.

Emerging patterns in uncertain times

Once the group started to grow, the number of daily messages exploded. This made it increasingly hard to communicate efficiently, as some topics would be covered repeatedly, for an endless number of times. It was really difficult to know exactly what was needed at any given moment. But soon, several focused workgroups spun off to create their own channels, inviting those interested in their specific topic to hop on board.

Many doctors and enthusiasts were also invited to join the conversation on Telegram, but the groups could be quite noisy and confusing for people who were new to the platform. David Cuartielles, co-founder of Arduino, created a specific forum (Foro A.I.RE) for a slower-paced conversation, distilling the most relevant facts about the topic. Foro A.I.RE attracted some 4,000 individuals within the first month, sharing papers, news and even reference designs for ventilators.

On Telegram, the number of topics was expanding organically, although ventilators still topped the list. Reesistencia Team announced they would start working on an open source ventilator based on a Jackson Rees type of valve (hence the name “Rees-istencia”). On March 16, they shared the initial design of Reespirator 23, which included a large 3D-printed piece to press the valve. They launched an open call for makers to start the lengthy process of printing these pieces.

This call sparked new regional channels on Coronavirus Makers, working to produce the pieces locally. As most components of the original design were open source and based on widely available Arduino boards, the initial idea was to produce the ventilators in a distributed way, near the hospitals in need.

Another priority topic on the channels was Personal Protective Equipment, as the urgent need for PPE soon emerged as one of Spain’s biggest challenges. As the spread of Covid-19 reached new peaks, news reported that Spain was the country with the most infections among healthcare workers. Makers immediately started working on all kinds of protective gear—goggles, masks and the ever-popular face shield designs.

On March 16, a publication in the forum provided scientific evidence on the usage of face shields to extend the lifetime of masks and prevent large virus-infected droplets from reaching cloth protections and the eyes of medical personnel. In Oviedo, Reesistencia Team had finished the prototype and was waiting for a lung simulator to start testing. Makers were eager to help 3D-print pieces, whether for the ventilator or any other project.

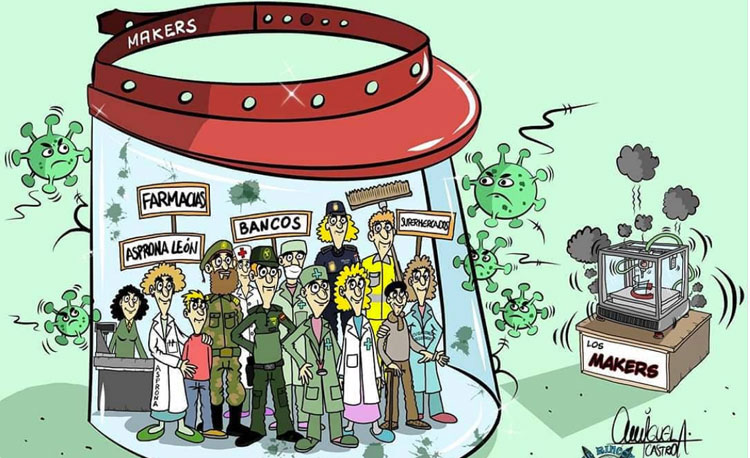

Illustration in El Rincon de Miguel highlighting makers’ role in printing face shields to protect essential workers. Photo: D.R.

Several makers started creating and sharing face shield designs in the Telegram groups. These shields were printed by makers all around Spain and given to neighbours who worked in hospitals. This act of kindness allowed for extremely rapid feedback loops. Nurses and doctors would use them during the day and then offer insights about how to improve them and make them more comfortable.

By the end of the week, every region in Spain had large numbers of makers producing face shields and delivering them to hospitals. Given the high volume of this makeshift equipment being used in hospitals, some people started asking questions about the quality of materials used, standards, safety, etc. Now under new scrutiny, local groups sought validation from their respective authorities.

Some regions, like Canarias, authorized the face shields, following standard work safety procedures, until other certified pieces were available. Madrid initially authorized the use of 3D-printed face shields on March 24, but then inexplicably reversed its decision on March 28. This movement sparked a huge controversy, as no alternative pieces were available for medical personnel. How could local authorities possibly prefer that doctors and nurses continue working unprotected rather than authorize 3D-printed parts, if only temporarily?

Fortunately, in other regions such as Navarra, the local government contacted the maker group directly and even offered to help with supply and distribution. Valencia followed suit, authorizing a specific 3D-printed model. All this time, the Coronavirus Makers group responded organically, adapting to evolving conditions to continue supporting medical personnel and other collectives in need.

For example, on March 30, the Spanish government halted all activity by non-essential workers, to prevent additional movement during the Easter holiday. This put additional stress on providers of raw materials and alternative transportation. One week, face shields would be delivered by volunteers, the next week, it could be by taxi drivers, and during the most extreme lockdown, even police and military members participated in the distribution network!

By the end of the first wave, on June 10, about one million face shields had been produced and distributed in Spain by volunteer makers across the country. A final design has been approved on a national level, both for 3D-printing and injection molding, so that everyone can produce an open source 3D-printed face shield that is certified in all regions.

Local Civil Protection and Red Cross teams supporting distribution of face shields from Fablab Cuenca. Photo: D.R.

Fablabs, makerspaces and other pre-existing collectives

But what is the relation between the ad-hoc Coronavirus Makers network and other maker groups and spaces that existed before the pandemic? Although the response is quite diverse, with different responses in each region, most fablabs, makerspaces and other institutions have been extremely active in fighting the pandemic and contributing supplies for local needs.

Fablab Cuenca and Fablab Mallorca participated as local coordinators for the Coronavirus Makers groups in their regions, supporting other makers and helping with logistics and equipment. Fablab Bilbao and Fablab Leon produced new designs for face shields using laser cutters, complementing the production of local maker groups with thousands more units. Fablab Xtrene (Almendralejo), Tinkerers Fablab (Castelldefels) and Fablab Sevilla responded to needs through their pre-existing networks.

Maker collectives such as Sevilla Maker Society produced PPE as well, involving unusual partners such as the Betis Football Club to help with distribution. Makespace Madrid has been working on an open source ventilator, while providing PPE to its neighbours. In some particular cases, fablabs within larger institutions such as universities have not been able to use the spaces, because of local regulations and mandatory stay-at-home orders. Their members have generally contributed their time and personal networks to support the local coronavirus groups.

Communication among all these spaces was possible from the start thanks to pre-existing communication channels. Through the shared WhatsApp group for CREFAB, the Spanish Network of Digital Creation and Fabrication (Spaces) shared news, organized local needs, best practices, etc. Other digital fabrication organizations such as Ayudame 3D and FabDeFab stopped their regular activities to help produce PPE, working with their partners and volunteers, supporting the larger cause, while retaining their own identity/brand.

Fablab Mallorca, acting as regional distribution center, inundated with 3D-printed face shields produced by volunteer makers. Photo: D.R.

After three months of lockdown

Evolving to adapt to current needs during the past three months, Coronavirus Makers has gone on to produce many other types of PPE. One of the most popular is the “salvaorejas” (ear-savers), a flat piece that secures the straps behind the head instead of around the ears when a mask is worn for an extended period of time. Coronavirus Makers also now has a large group dedicated to textiles, working ethically with workshops and small shops to produce PPE and creating open source designs for DIY masks called +K rilla and +K Origami. A distributed group is producing ICU grade masks using injection molded silicone.

Other groups have created software such as mobile applications to manage the logistics of deliveries or to encourage healthy habits, such as Higiene Covid-19, promoted by the Ecuadorian government. Spain is expected to end its State of Emergency on June 21. Since the end of May, demand for PPE has dropped, and most people are either going back to their regular work and/or helping other people in their neighborhoods or in other countries. More than 15 coronavirus maker groups in other countries, mostly Spanish-speaking ones, are currently trying to replicate some of these processes to fight Covid-19 in Latin America.

So what happened to the open source ventilators?

While Spain saw a groundbreaking number of projects to build open source, low-cost alternatives to help critically ill people breathe, the main challenge with so many ventilators was that the approval steps, requirements, etc., were not clearly defined. Some countries, like the UK, published a document with clear requirements, while the U.S. published special guidelines with less stringent FDA requirements for approval. In Spain, however, there were no such special provisions, so each team working on a ventilator was pretty much on their own.

By the end of March, A.I.RE, through COTEC Foundation, managed to organize an open call with the people in charge of the certification process at the Spanish Agency of Medicine and Health Products (AEMPS). During that call, 115 people representing more than 35 projects could ask questions about the certification process. All this information was then published to officially guide the development process. A complete video conference on ventilator certification was organised with with AEMPS and multiple R&D teams.

To get a prototype approved for clinical trial, it was required to pass tests with a lung simulator, animal trials experiencing severe respiratory distress and electromagnetic compliance. Once reviewed, it would need a final seal of approval from the ethical committee at the hospital. Then it could be used, if and only if, there was no other certified ventilator available for the patient (see this article on the Arduino Blog for more details).

Under these rules, seven prototypes managed to pass all the tests within the following two weeks. Several of these teams included members from large companies and/or research centers, with expertise in certifying clinical equipment. Others however, coming from maker/designer backgrounds, managed to have their product approved and even manufactured by large companies, offering maker friendly versions such as OxyGEN.

While creating a ventilator from scratch is a herculean task, a critical mass of individuals joined this race against the clock. In less than one month, Spain went from zero available ventilators to several ready-to-use devices. By the time this process was over, the impact of lockdown had reduced the number of patients under intensive care. The only two companies producing certified ventilators increased their production tenfold in the past month, with support from the Ministry of Industry, so there was much less need for DIY/maker respirators. Reesistencia Team passed trials of their device with animals, but so far no AEMPS-approved version has been publicly released.

In the tradition of open source, some of the projects have forked or merged. For example, on April 24 Reespirator 2020 was announced as a fork of Reesistencia Team’s Reespirator 23. In this repository, they explained that, even though none of these ventilators would be mass manufactured in Spain, they plan to keep developing them to benefit other countries in need.

Initial prototype for ReesistenciaTeam Ventilator. Photo: D.R

Other Spanish initiatives

During these last three months, makers in Spain have connected with countless companies, institutions and individuals sharing the same goals. Ayuda Digital COVID (formerly known as TIC para Bien), contributed their IT expertise to help create elements of the digital infrastructure. Frena La Curva (Slow down the curve), focused on social aspects, connecting offers and demands from underserved communities. European Cluster Alliance connected Spanish initiatives to a larger pan-European network, promoting cross pollination of ideas among European peers. COVIDWarriors facilitated networking with common goals and provided several hospitals with open source robots for clinical trials. Sharing a common goal enabled collaboration on multiple scales, at speeds that were unthinkable a few months ago!

Final gratitude

All the work done by the Spanish maker initiatives would have not been possible without the support of hundreds of companies and individuals that have supplied raw materials, transportation and other elements to channel this maker solidarity. Special gratitude to all our medical personnel: doctors, nurses and everyone involved in mitigating the severe impact of the Covid-19 pandemic!

Cesar Garcia Saez

published in partnership with Makery.info

Follow on Cesar Garcia Saez on La Hora Maker.

More on Makerspace Madrid.

Original call for makers on Twitter

This series of surveys is supported by the Covid-19 emergency fund of the Daniel and Nina Carasso Foundation.