between evolution and sanctification

Can text be saved by the book? As writing and reading practices evolve within the digital environment, French theater defends itself above all logic of the printed text…

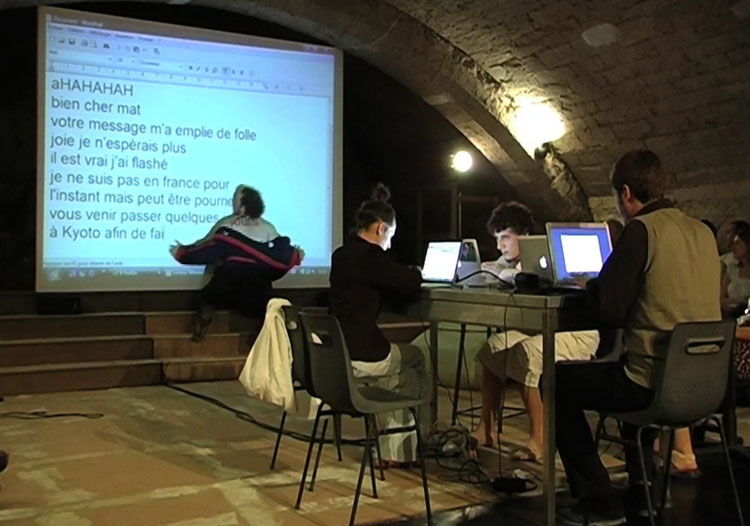

Illusion.com, 2009. Photo: © La Chartreuse de Villeneuve-lès-Avignon

Theater of text or theater of the book?

Now that the profound changes which have transformed writing and reading practices have finally been acknowledged, theater is more than ever reaffirming literary values linked to book culture as a way of legitimizing itself. While new artistic practices develop in relation to digital technology, « text » stands as the last bastion of theater. Or perhaps it should be the book—after all, those who support theater of text refer primarily to theater of the book. In this context, it is sometimes difficult to convey that textuality is evolving on new formats which contribute to renewing and opening up theater art.

Claiming the primacy of text accompanies a complementary discourse that values the interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary and transversal natures of theater, but only to assign them ancillary roles, where issues surrounding text are most often diluted. Recent developments in writing have thus troubled our cultural « networks of discourse » structured more around collection of data than openness to ideas. There is no specific difference by which they can be indexed and categorized; instead they produce new effects, which have yet to be evaluated. Therefore, a historical approach is best suited to renew these issues and put them into perspective.

It was in this context that I directed for four years at La Chartreuse – Centre National des Écritures du Spectacle a project entitled Levons l’encre, in order to give perspective to developments in textuality and writing for theater. Within a cultural structure dedicated to writing, it may seem only natural to take into account current writing technologies, as well as necessary to adapt to the evolving practices of authors and artists. While the myth of the writer’s hand scribbling away on a blank page still exists, the fact is that the vast majority of authors today write on a computer.

This approach aims to radically re-examine the issue of text in theater by confronting it with the history of writing and its current developments. It suggests that text, far from being one of the fundamentals of theater, is changing in ways that have a crucial effect on all theatrical components. Separating text from print denounces our typical confusion of text and book. If we replace the notion of theater of text with theater of the book, we will no doubt see more clearly. The problem is that many people tend to sanctify theater in relation to digital technology—through « text », although in reality through print—rather than explore ways in which new forms of writing can contribute to mapping out new territory for theater.

Writing spaces beyond the book

If text written for theater was not originally presented in the form of a book, we can just as well imagine dramatic text that is not printed. Has print influenced theatrical practices? If so, what is it like to write for theater without following the logic of print? If digital technology offers new forms of writing, can it create new spaces for writing that call for new forms of composition and other ways of making theater?

This angle of attack goes against the usual ways of thinking. While it overlaps in several points the post-drama debate, which has contributed so much in recent years to esthetic debates concerning theater in Europe, it filters the topic through the materiality of writing. It does not specify theatrical forms related to images and screens on the stage. Writing and reading media are all part of the debate on writing for theater. In short, by revealing a blind spot, we attempt to spotlight a new territory to be explored, both invisible and ubiquitous, where writing and reading in digital environments are nothing short of routine.

As we were experimenting with these topics at La Chartreuse, it occurred to me that we could try to reread the history of theater through successive changes in the history of writing. If historians put new writing modes into perspective through the history of the alphabet and printing, have these textual milestones had any effect on theater?

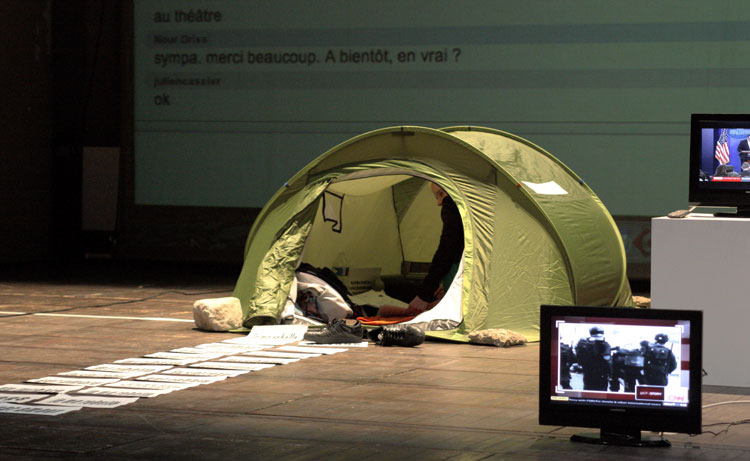

sonde03#09 – Chartreuse News Network. Photo: © Alex Nollet, La Chartreuse de Villeneuve-lès-Avignon.

Several works by historians and anthropologists have made evident a constitutive and structuring relationship between writing media and the history of theater practices. The emergence of new media for writing invites us to reconsider the articulations between writing and theater that underlie and organize theater practices. We have developed this historically themed research elsewhere, placing particular emphasis on the complex articulations between theater and print, which are key in understanding the extent to which digital technology is deconstructing practices and devices linked to print.

While theater persists in theorizing, administrating, gaining expertise and perceiving itself primarily through the framework of print, a coherent series of mechanisms that link page and stage, and in fine a way of instituting theater practices, is obsolescent. After the specific typographic conventions of the drama script, we are discovering a burst of diverse materialities of writing for theater. Some authors—to mention only those in French theater: Noëlle Renaude, Matthieu Mevel, Sonia Chiambretto…—are digitally reinvesting print and exploring new materialities of drama writing that incorporate typographic wordplay, graphic design and singular layouts.

In parallel, some authors are experimenting with new media writing online, in social networks, projected on various types of screens on stage, on mobile devices. La Chartreuse encouraged this exploration of the field by commissioning four authors to create an online work (Illusion.com by Joseph Danan, Sabine Revillet, Eli Commins and Emmanuel Guez), by producing an audio journey by Célia Houdart, and by supporting Eli Commins’ Breaking, which uses Twitter testimonies to write about world events such as political resistance in Iran, the earthquake in Haiti, etc.

Opposing the affirmation of authorship in theater is the reality of multiple forms of practices, which lead the author to develop the text directly in relation to the physical and technological environment of the stage. While print distanced the author from the stage, new media for writing have reintroduced the author into the theatrical creative process. They reactivate theater as a collaborative process, neither structured hierarchically around the author’s message, nor directed and controlled remotely by the text. Far from institutionalized routines and lack of curiosity, these transformations call upon a new dynamic that welcomes experimentation, research and innovation.

Theater as a metaphor of the computer, not the book

The evolution of writing is also the evolution of reading. The viewer as displaced reader—more precisely, reader of books—is joined by the viewer as displaced TV viewer, moviegoer, Web surfer, hypertext reader or gamer.

More generally, we can compare today’s emergence of theater within the digital environment—from control room to communication, from set design to video archive—to the way it once took possession of print. The revived motif of theater of the world, which leads the way for theater and books, revolves around the idea of the stage as a metaphor of its technological, media and cultural environment, where it is critically confronted.

Theater of the book remains the central paradigm of theater today. But it can no longer be the only paradigm. As a metaphor of the book, the stage is becoming more and more of a metaphor of the computer, or even a metaphor of the relationship between the two, influenced by a new relationship between writing and orality. Linearity or simultaneity/discontinuity, prioritizing stage materials to serve the text or hybrid writing, remote or active participation of the audience, constructing meaning or constructing a sensitive and intelligible experience… are all contrasting cultural conceptions of the theatrical arts. They refer to the way the media informs our practices.

Theater coordinates writing techniques, ways of thinking, diverging perceptions. It’s a rich asset. It reflects the complex situation of writing within our society. But it can also be an invaluable vehicle to explore the evolution of writing throughout our society.

Franck Bauchard

researcher and critic, artistic director of La Chartreuse (2007-2011)

published in MCD #76, “Writing Machines”, march/may 2012